Investigating the geographic and ethnic inequalities in the consequences of COVID-19 at the small area level

NIHR SPHR Summer Internship Scheme in Public Health Research

Supervisor: Alex Alexiou

Introduction

Many believe that the COVID-19 pandemic is a ‘great equaliser’, affecting anyone – even the most privileged. However, findings suggest that some communities are at greater risk because they are unable to protect themselves like other communities do. The adverse consequences of the pandemic are falling disproportionately on more disadvantaged groups like those from ethnic minorities and has exacerbated the already pre-existing health inequalities in ethnic minorities. Reports from the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) show that people from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups are up to 5 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than White British people. These groups remained at higher risk even when adjusting for factors such as location, deprivation or pre-existing conditions, suggesting that the underlying reasons might be more complex. Evidence shows this is not just experienced in the UK, but globally, such as in the USA.

It is evident that ethnic minorities are at greater risk to the pandemic, but the reasons and mechanisms remain unclear. Certain socio-economic characteristics result in such ethnic groups having a higher infection rate, which are usually closely correlated with higher deprivation. One underlying factor that was common brought up among academic literature was overcrowded households. Studies from the English Housing Survey suggest that 30% of Bangladeshi households experience overcrowding, 16% of Pakistani and 12% of Black households, this only compares to 2% of White British households. When compared to the White British population, ethnic minority groups in the UK are more likely to reside in socio-economically deprived areas and are more likely to face poverty and unemployment. Deprived neighbourhoods are more likely to have multi-occupancy residences and smaller houses with little outside space, as well as higher population densities. These factors will likely increase COVID-19 transmission rates as they have reduced ability to socially distance. Another factor to consider is the relationship between mortality and age. Age is widely accepted as a key factor in COVID-19 deaths. Ethnic minority communities however are relatively younger; according to the 2011 Census, the White ethnic group had the highest median age at 41 years, compared to e.g. those from Mixed background with 18 years, suggesting that mortality from COVID-19 should be lower in such communities compared to others.

Research also shows that ethnic minorities are associated with having higher levels of insecure employment. Whilst being lower paid workers, they are usually more likely to be “key workers” and unable to receive furlough or work from home. As a result of being in an environment with more viral exposure, individuals are more likely to spread the disease when they return home due to being in closer contact to family members. Structural racism and discrimination could contribute to working in lower paid jobs or on insecure contracts, living in crowded housing conditions, and having fewer resources for health. These factors may have increased their exposure to the disease. This could exacerbate the outcomes of COVID-19 when ethnic minorities are less likely to have the same level of access to healthcare, due to e.g., language barriers.

All these factors may have contributed to communities with a greater proportion of residents from ethnic minorities backgrounds having a significantly higher COVID-19 mortality rate, alongside communities experiencing deprivation. This study will further investigate the correlation between ethnic minorities and the consequences of COVID-19 and explore the relationships of ethnicity with a number of risk factors, as outlined in the literature, at the local level.

COVID-19 mortality patterns at the local level

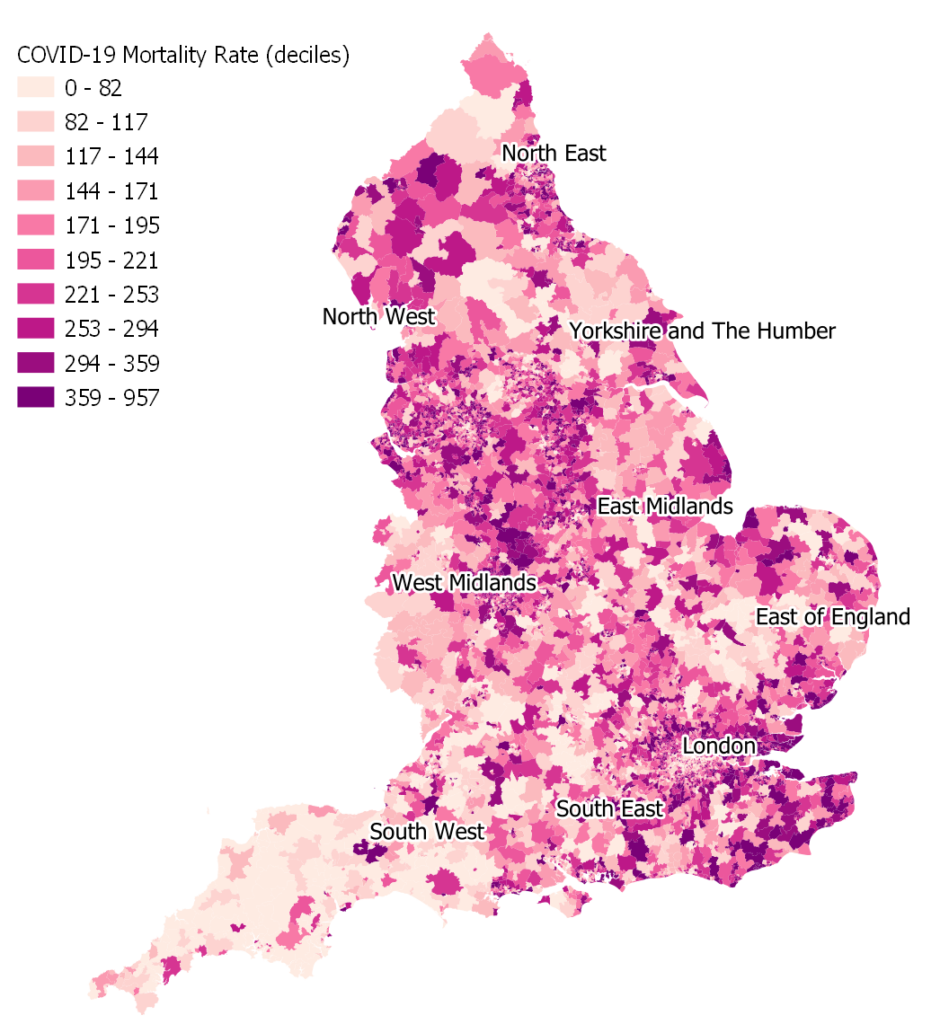

Figure 1 illustrates a map of COVID-19 mortality rates (per 100,000) across all Middle Super Output Areas (MSOAs) in England for the 14 months between March 2020 and April 2021. It is evident that areas experienced different mortality rates, with the top 10% having almost ten times the average mortality rate compared to the bottom 10%.

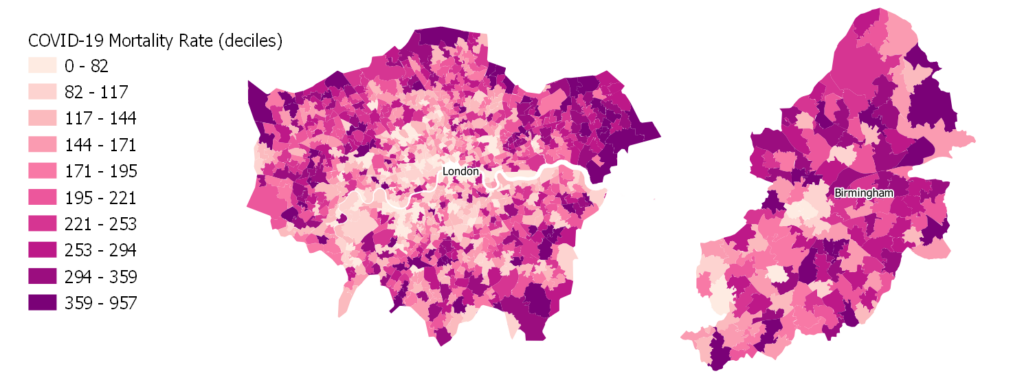

While it is difficult to discern any emerging patterns at the national level, figure 2 provides a few examples by looking closer at the areas of London and Birmingham. It is evident that within London, the mortality rates are much lower within the centre and when moving towards the outskirts the mortality rates increase. The explanation for this may be that one can find much younger populations within the centre, for example the large student populations and young urban professionals compared to the periphery, since the risk of mortality due to COVID-19 is heavily associated with age. In the area of Birmingham, the pattern seems more complex. Birmingham is one of the most diverse areas in terms of ethnicity, and therefore this might be an important factor for the emerging patterns of mortality in the area. In general, the map below shows higher levels of mortality in the north of Birmingham, while lower levels in the southwest, but the pattern is not clear, suggesting there might be a variety of factors at play here, such as age, ethnicity, and deprivation.

How is mortality due to COVID-19 associated with ethnicity?

As we discussed earlier, mortality risk due to COVID-19 has been associated with a range of factors. A study of the association between area characteristics and mortality rates can help us explore the place-based drivers in these health inequalities. In this analysis, we will focus on the impact of ethnicity in mortality patters.

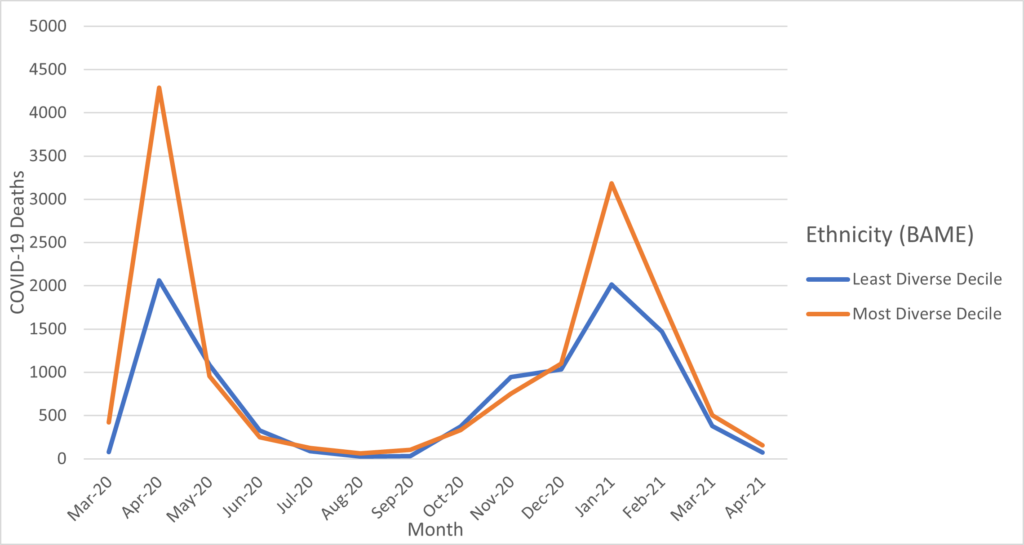

First, we use monthly data supplied by the Office for National Statistics to graphically explore the trends between ethnicity and COVID-19 mortality rate for all MSOA areas in England. Data were provided by ONS. The trends of deaths by months between the most and least ethnically diverse decile of areas is shown in figure 3.

There is a definite association between the most ethnically diverse areas and higher mortality rates. While both areas exhibit the same tendencies, such as peaks and troughs. It is apparent that the most ethnically varied places suffer the most from the repercussions, resulting in a higher number of deaths. It is also interesting to note that significant differences between areas is only seen during the two peaks of the pandemic waves. A plausible explanation for this pattern that is worth looking into is that perhaps individuals living in more ethnically diverse areas were unable to shield themselves and self-isolate as much as population in other areas, due to e.g., work and living conditions. However, it is crucial to note that the data only includes total deaths and not age-adjusted mortality, so these trends may be misleading.

Since there is no evidence of any biological factors between the various ethnic background and COVID-19 mortality, we can conclude that there must be other population characteristics associated with ethnic minorities that contribute to higher mortality rates. In this instance the analysis will consider the associations between ethnicity and age, deprivation, and overcrowded households. We explore these associations below, showing the median values and distributions of said characteristics within the least of most ethnically diverse deciles of areas.

For ethnicity measures, we use the proportion of the population from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic backgrounds, based on Census 2011 data supplied by the Office for National Statistics. Data on overcrowded households, deprivation (2019 Index of Multiple Deprivation), and population age were supplied by ONS and compiled by the Place-Based Longitudinal Research Resource.

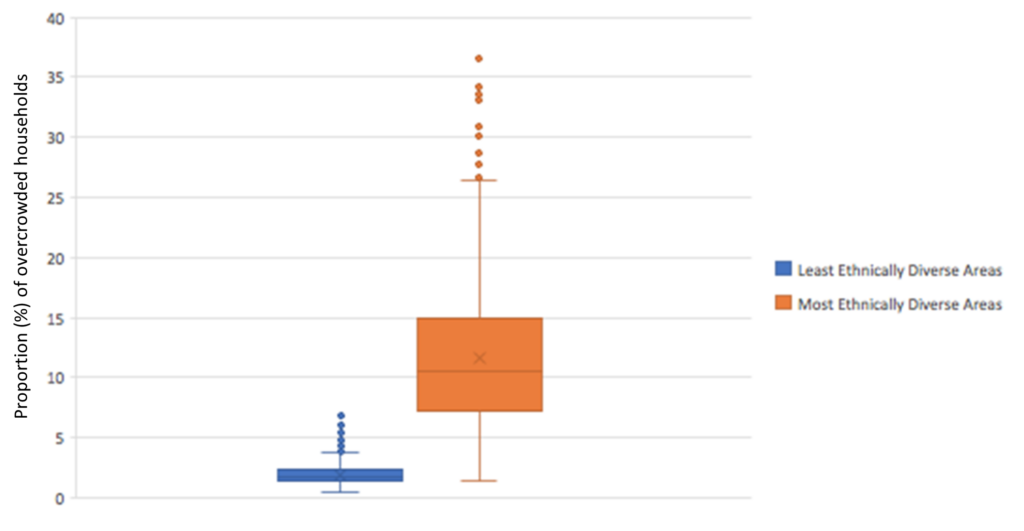

The graphs shown in Figures 4, 5 and 6 all show significant differentiation between our underlying characteristics and ethnicity, and thus demonstrate important relationships we must take into consideration when exploring the effects of ethnicity in the observed mortality rates. As discussed in the relevant literature, people from a BAME background may struggle in terms of social distancing due to smaller houses with large families and therefore leads to the effect of overcrowding. Figure 4 evidently shows a much lower median value and interquartile range for the least ethnically diverse areas in terms of the proportion of households defined as overcrowded, with a median value of 1.75%, compared to the most ethnically diverse areas, with a median value of 10.5%. This clearly illustrates that the factor of overcrowding is highly associated with ethnicity and likely plays and important in the mortality patterns observed.

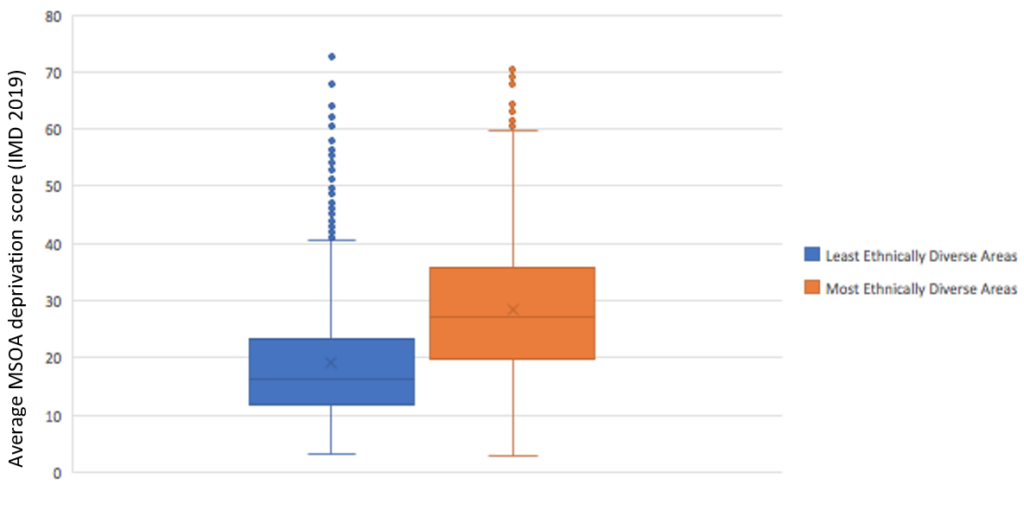

Figure 5 explores the relationship between deprivation and ethnicity. Mortality rates due to COVID 19 is highly associated with deprivation, as discussed previously. As it was stated how ethnically diverse areas are usually more associated with higher levels of deprivation. Thus, we can evidently see the high correlation between social factors and mortality.

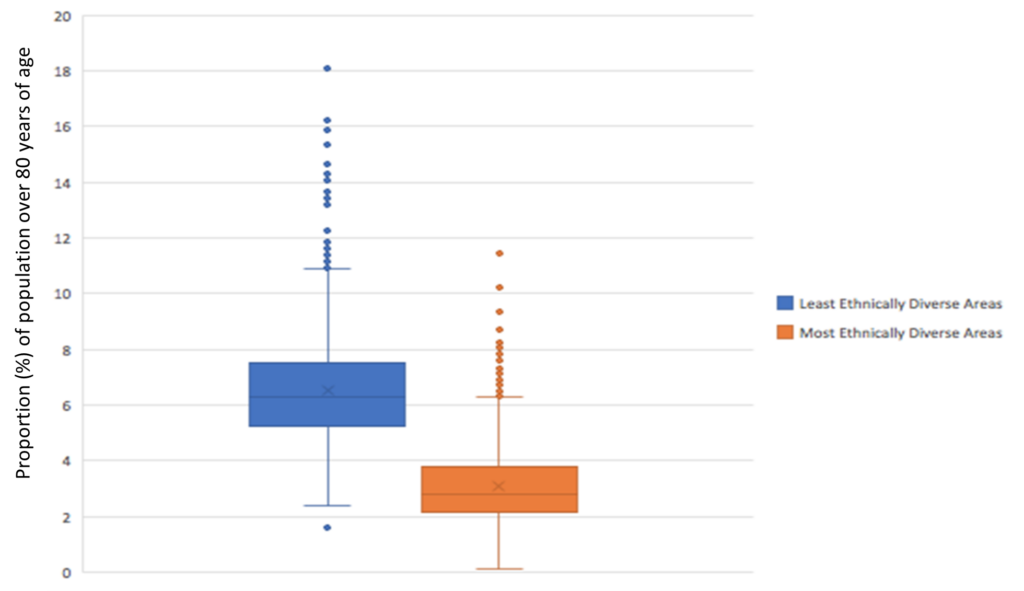

On the other hand, Figure 6 shows that in the least ethnically diverse areas there is a much older demographic, with a median value of 6.3 % compared to the most ethnically diverse areas with a value of 2.8%. In this context, one would expect lower mortality rates in the most ethnically diverse areas. Since more ethnically diverse areas have higher rates of mortality compared to less diverse ones, we would argue that despite the age profile of such areas, other socioeconomic characteristics greatly offset the impact of age in the observed mortality rate.

Other factors might also be worth exploring, like occupation. However, it is hard to categorise exactly what occupation correlates with higher mortality rates, especially when considering the current data availability and in particular the existing ONS categorisations. There is simply not enough granularity in the available data to perform such analyses, as some specific occupations have been associated with higher mortality rates (e.g., taxi drivers, social care workers).

Discussion

Ethnicity is a significant element of this pandemic. Ethnicity clearly plays a part in the morality rates we’ve witnessed in the last one and half years because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The underlying reasons are many; for instance, persons from ethnic minority backgrounds are clearly associated with higher levels of impoverishment, among others. Our review of the relevant literature highlights the factors that seem to be the cause for this disproportionate effect on people of ethnic minorities.

As we can see from our study, the ability to shield oneself seem to have impacted mortality rates, particularly during the pandemic peaks. The results demonstrate where current policies should focus on and what can be done in the future. In this study we looked at specific factors that are possibly associated with this observation, such as the relationship between ethnicity and overcrowded households and deprivation. Based on this analysis, it is relatively clear that the pandemic’s effects are not felt uniformly, and socio-economic factors play a significant part. Although there is a substantial association with these social aspects, we have not looked into other factors that may be relevant, such as occupation. Unfortunately, analysis with these factors could not be carried out due to data availability and methodological difficulties. This could be a study gap that we should investigate in the future.

It is worth noting that the long-term repercussions of COVID-19 to those from a BAME background is an interesting subject that hasn’t been studied extensively. It is critical that government action should be focused on the underprivileged as we move forward. This can be accomplished by putting a higher emphasis on examining racial imbalances in the pandemic’s economic fallout, adopt policies that target health inequalities and improve access to health care for everyone.

This project is funded by / supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research (Grant Reference Number PD-SPH-2015-10025). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.