What did local government ever do for us?

Levelling up health will only succeed if we invest across the whole of local government.

By Alex Alexiou, Ben Barr, Kate Mason, Davara Bennett, Katie Fahy and David Taylor-Robinson.

The Government has committed to level up the country and ensure that no place is left behind. What will be levelled up? It is not always clear, but surely it should be the most important thing in most people’s lives – their health. After all, the health of the people should be the highest law.

There is strong evidence that investment across local government, is crucial for levelling up health. This means investment in children’s, housing, cultural, environmental and planning services, as well as in specific public health and social care services. Investment in each of these areas has been cut over the past decade, and cut most in the places where need is greatest, reversing the trend of the previous decade. Whilst this was a disaster for public health even before the pandemic struck, this natural experiment, has taught us one thing – the importance of investment in local government for public health. The research outlined below shows how disinvestment in each of these service areas, has come at a cost, to the detriment of public health, further leaving behind those places where livelihoods were already most disadvantaged. This led to increasing infant mortality and a dramatic widening in health inequalities, that has been made worse during the pandemic. The message is clear: to reverse this trend, to level up, we need to re-invest across local government; but importantly, invest most in those places with the greatest need. The upcoming spending review is an opportunity for the government to put its money where its mouth is and truly level up.

Levelling down – the unequal cuts to local government and stalling life expectancy.

Since 2010 central funding to local government has reduced by 50%, leading to a 30% reduction in spending power, the equivalent to £12 billion. As poorer areas are more reliant on central funding, as they are less able to raise income through local taxation, this significant reduction has affected poorer areas the most, where the need for services is greater. The map below shows that many of the the places that have lost the most are in the North, and this regional variation closely mirrors maps of deprivation and poor health.

Figure 1. Change in local authority spending power between 2010 to 2018 in real terms. Data Source: DCLG.

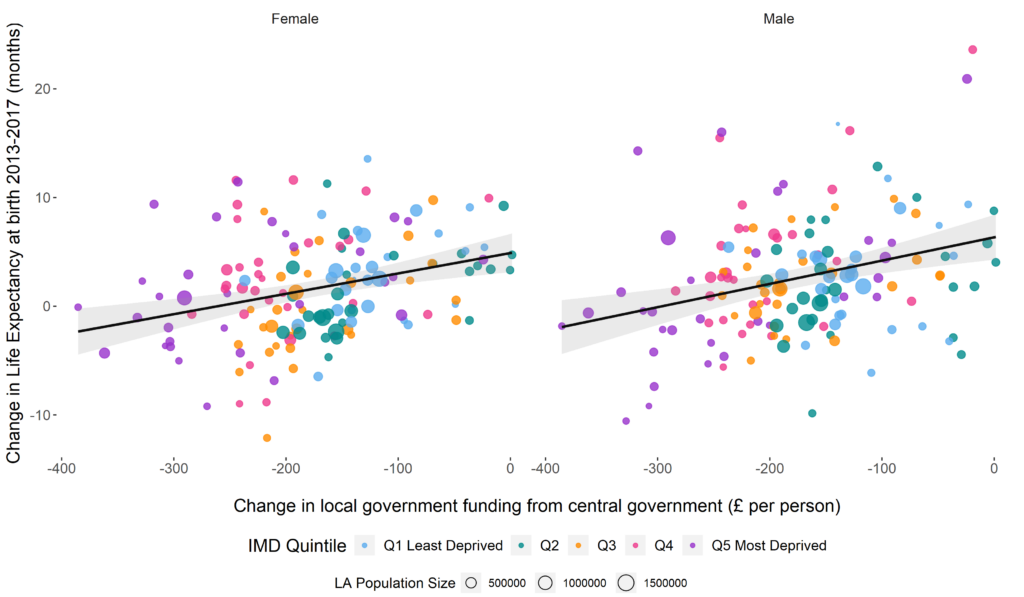

Before the pandemic, it was widely recognised that improvements in life expectancy had stalled over the last decade and inequalities were widening. Our analysis, published in the Lancet, shows how cuts to local government funding made a significant contribution to these adverse trends in mortality. Over a 5-year period we show that these cuts led to an estimated 10,000 additional deaths in England, in people under 75 years of age, compared to what would have been the case if local government funding had not been cut. As funding was cut more in the most deprived local authorities, this had a greater effect on mortality, widening the already stark health inequalities (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Association between change in central government transfers to each local authority area and change in life expectancy for men and women between 2013 and 2017.

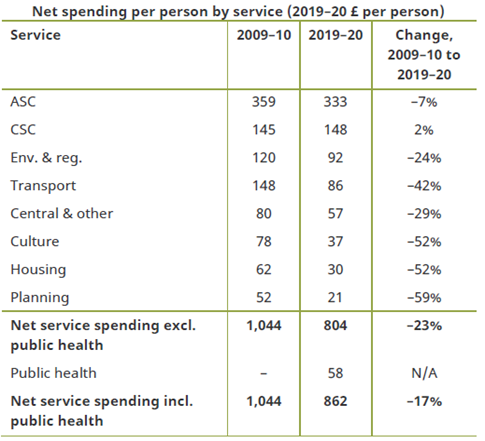

It is perhaps not surprising that such massive cuts had such a large impact on health. With such financial constraints, councils had no other option than to cut back on the services they delivered. But what services have councils been forced to cut? These cuts were not evenly distributed among service areas. In general, because councils have statutory responsibilities to provide some services – such as adult and children’s social care – they have maintained funding in these, whilst cutting discretionary services. For example: transport, housing, leisure, environmental, cultural and planning services (see table 1). Unfortunately, these are the very services that tackle the root causes of health inequalities.

Table 1. Change in local authority spending by service area.

Investing in the best start in life.

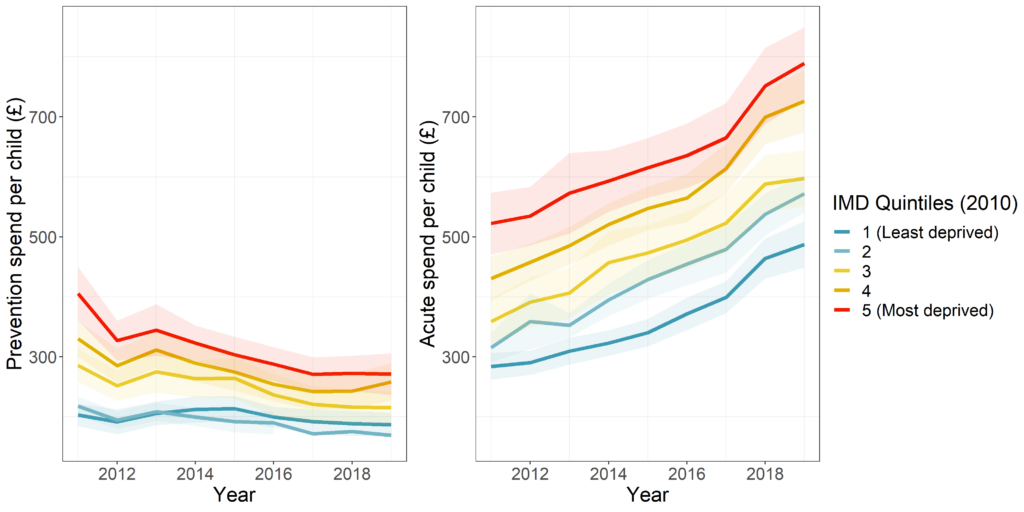

Multiple reviews have highlighted that one of the most cost effective approaches to reducing health inequalities is to invest in children. One might think from the table above that because spending on children’s services actually increased between 2009 and 2019, that children have been protected from a decade of austerity. But this is very far from the truth. In fact, there has been continuous disinvestment in the very services that Sir Michael Marmot in his 2010 review of health inequalities recommended investing in – giving every child the best start in life. Local government spending on preventative early years and youth services (including Sure Start) fell by 21% over the past decade, with these declines being greatest in the most deprived areas (see figure 3).

Overall spending on children’s services increased because of a massive rise in the number of children being taken into the care of the local authority – spending on this increased by 68%. Being taken into care as a child is a marker of severe deprivation, and those children tend to go on to face adversity throughout their lives. We have increased investment in trying to pull drowning people out of the river, whilst cutting the services that prevented them from falling in the first place.

Figure 3. Trends in local authority spend on prevention services for children and young people and spend on safeguarding and children taken into care, by deprivation level in England.

Our research has shown that these increases in children being taken into care have been greatest in the most deprived areas, the very places where preventative services have been most severely cut.

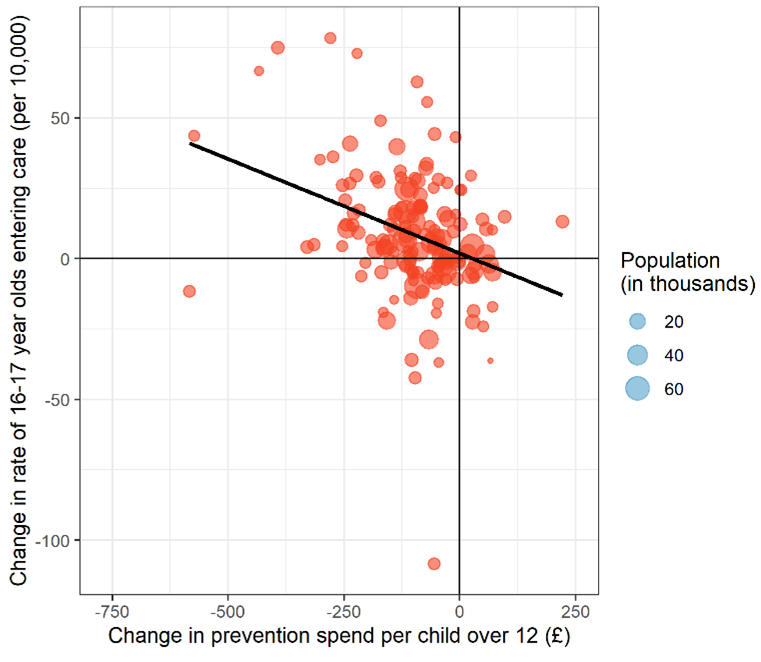

A further study of ours has shown that reductions in spending on preventative services for adolescents is directly linked to rising rates of 16 and 17-year-olds entering care (see figure 4). Every £10 decrease in prevention spend per child was associated with an estimated additional two 16-17 year old children entering care per 100,000 per year. In total, we estimate that an additional 1,000 children aged 16-17 were taken into care, over 8 years, than would otherwise have been expected had 2011 levels of prevention spend been sustained. This added an extra £60 million to councils’ care bills, wiping out any savings from cutting prevention spend. If these cuts in prevention services are not reversed, they will contribute to spiralling costs in the future.

Figure 4. Associations between changes in local authority prevention spend on adolescents and changes in adolescents entering local authority care, between 2011 and 2018.

The positive effect of prevention, and the negative impact of reducing prevention is clear. This is particularly the case for early years services, such as Sure Start children’s centres. Children’s centres have been one of the successes of government policy in the UK, providing joined up support for parents and children when they need it most. A study by the institute for Fiscal studies (IFS) has shown that investment in Sure Start reduced hospital admissions during childhood, especially for children living in the most deprived neighbourhoods. But cuts to preventative children’s services outlined above have led to the closure of many Sure Start centres. Evidence of the adverse consequences of this decision, is now emerging.

In our recent study we show that cuts in spending on Sure Start has contributed to an increase in childhood obesity. We estimate that several thousand additional children became overweight or obese compared with the expected number if spending levels had remained at 2010 levels. Reinvesting in Sure Start should be part of the government’s strategy to reduce childhood obesity. These cuts are likely to have also contributed to the recent widening of the obesity gap between the least and most deprived children. Cuts to spending on Sure Start have also been linked to worse child development as children start school.

The health impact of local government housing services.

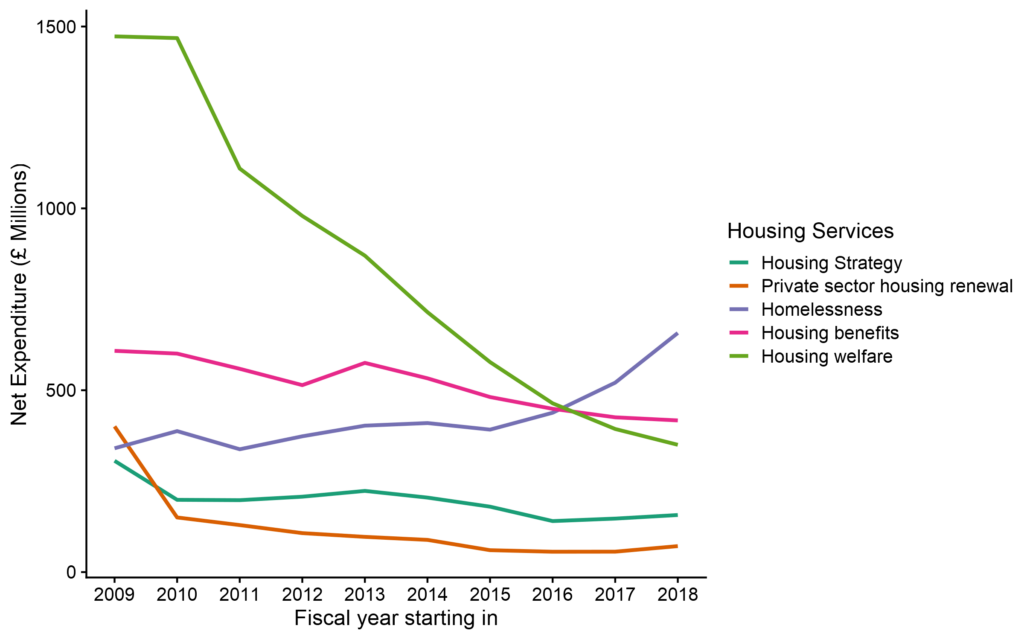

The link between housing and health has long been recognised. Whilst local governments, are less involved, than they use to be, in the direct provision of council housing, they continue to provide critical housing support services – including temporary accommodation, housing advice, homelessness prevention, rent rebates and housing welfare. Housing is one of the areas of local government that has experienced the most severe cuts. Spending on housing services and homelessness prevention declined by over 50% in between 2009 and 2019.

Our analysis shows that these cuts have particularly affected housing welfare services, such as the Supporting People Program (figure 5). These programs provide housing support for vulnerable groups, such as people with poor mental health, women at risk of domestic violence, young people leaving care, or people with drug or alcohol use problems.

As we saw with children’s services, alongside these cuts in prevention we have seen increases in spending on acute adverse events. Spending on homelessness including temporary accommodation, has seen a significant rise, particularly in more recent years. The consequences and costs of the disinvestment in prevention has been severe. Street homelessness has been rising steadily, with numbers doubling between 2013 and 2018, and this has led to increased number of homeless people dying in recent years. Homelessness and substance misuse are often linked, and drug deaths have been rising steadily over the last decade, reaching record levels in 2020.

Figure 5. Trends in spending on local government housing services in England. Data source: MCHLG.

In a recent study, we showed that reductions in funding for housing services were associated with increased deaths from drug misuse, accounting for an additional 1000 deaths from drug misuse between 2013 and 2018, 7% of all drug-related deaths during that period. It is likely that local government’s inability to secure the appropriate accommodation for homeless individuals and households, and inadequate preventative, advisory and supportive services for vulnerable groups, has contributed to the recent increases in drug deaths.

The environment in which we live.

Local government is central to so much that makes places good places to live. Councils are the biggest investor in sport, leisure, parks, and green spaces, spending £1.1 billion per year in England. Providing opportunities for physical activity that are affordable for all is crucial for addressing health inequalities. Local authority sport and leisure facilities play an essential role in giving children the best start in life, with 72% of schools relying on public swimming pools to teach children how to swim. Our previous research has shown that by reducing the cost of using leisure facilities local authorities can have a major impact on levels of physical activity – and importantly increase the physical activity of more disadvantaged groups who have previously been the most inactive.

The urban green spaces, such as parks, playgrounds, and residential greenery that local governments develop and maintain can promote mental and physical health, and reduce morbidity and mortality. Local council libraries, museums and art galleries have also been shown to improve social cohesion, as well as providing educational opportunities, developing digital skills, assisting with job applications, and increasing employability. Environmental and regulatory services provided by local government also play a vital role in public health. These services are targeted at managing environmental health hazards, such as air and noise pollution, infectious diseases, and regulating industries. Further, local government’s planning and developmental services are responsible for community and economic development plans that influence local jobs, transport and living environments, all of which have important implications for health.

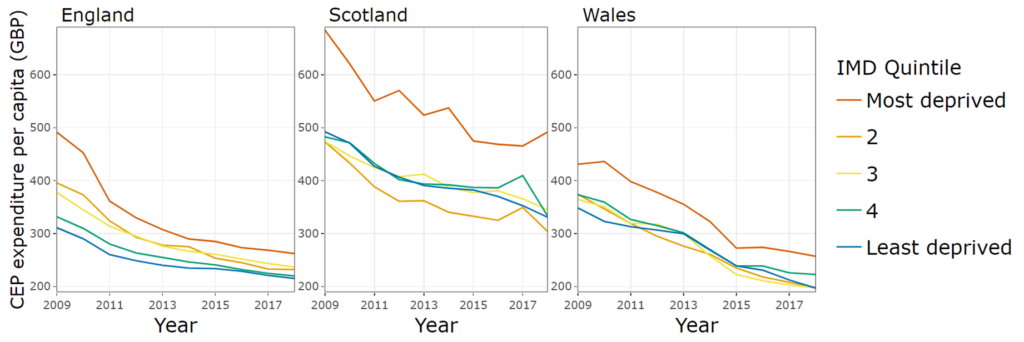

These Cultural, Environmental and Planning (CEP) services have also been cut by 50% during the last decade. Whilst similar cuts have taken places across the countries of the UK, it is only in England that these have been regressive, reducing funding most in the most deprived areas (see figure 6). The consequences for public health are likely to be severe and last for many years to come. For example, research currently being done by our group suggests that cuts to spending on CEP services may be associated with increased childhood obesity, particularly in more deprived areas.

Figure 6. Gross expenditure per capita on Cultural, Environmental and Planning services by country and level of deprivation.

What is to be done?

The evidence is clear that investment across local government reaps public health benefits and disinvestment causes harm. This is not just about investment in specific “public health” services provided by local government such as smoking session, sexual health or drug and alcohol services, although these have also been cut by £1 billion (even though investment in these services leads to greater benefits than investment in the NHS). Investment across the whole of local government is needed to level up health including investment in housing, children’s, leisure, cultural, environmental, and planning services.

The government has committed to level up health and ensure everyone has the chance to live happy and healthy lives. Boris Johnson called the widening differences in life expectancy between places an outrage. His predecessor, Theresa May, in her first speech as prime minister vowed to fight against this burning injustice. Unfortunately, under the stewardship of the past three prime ministers this health divide has increased, reversing the trend of the previous decade. The pandemic has led to a further dramatic deterioration in health equality, hitting the poorest places hardest, increasing the need for urgent action.

The evidence, we present here, shows that these differences in health can be reversed, by getting the right resources to the places that need them most. The upcoming spending review is the opportunity to do that, by investing in the conditions needed for a healthy life, investing in local government. To achieve the government’s ambition will require a reversal of the cuts to local government, but we also need to ensure resources are shared between places in proportion to their needs. The Government’s “Fair Funding” review aims to reform how local government funding is allocated to places, but it has suffered from multiple delays – first due to Brexit and then due to the pandemic. Initial proposals published in 2018 indicated that the Government planned to remove deprivation from the assessment of need for housing, cultural, environmental and planning services; we have shown that this would further widen the health divide and was justified based on flawed statistical analysis, further confirmed by an IFS analysis. The government is still analysing feedback from the consultation on that proposal. It is crucial that in assessing the relative need for council services that the drivers of poor health are considered across all areas of local government, not just public health and social care services.

The UK Government has declared that austerity is over and has committed to investing more to support places that have previously been left behind. This commitment has become increasingly important following the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s time to move beyond rhetoric to ensure fair investment in local government to level up health.

Further reading

Alexiou A, Fahy K, Mason K, Bennett DL, Brown H, Bambra C, Taylor-Robinson D, Barr B. Local government funding and life expectancy in England: a longitudinal ecological study. The Lancet Public Health 2021; 6: e641–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00110-9.

Bennett DL, Mason K, Schlüter DK, Wickham S, Lai ETC, Alexiou A, Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D. Trends in inequalities in Children Looked After in England between 2004 and 2019: a local area ecological analysis. BMJ Open 2020;10:e041774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041774.

Bennett DL, Webb CJR, Mason KE, Schlüter DK, Fahy K, Alexiou A, Wickham S, Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D. (2021). Funding for preventative Children’s Services and rates of children becoming looked after: A natural experiment using longitudinal area-level data in England. Children and Youth Services Review, 131, 106289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106289.

Higgerson J, Halliday E, Ortiz-Nunez A, Brown R, Barr B. Impact of Free Access to Leisure Facilities and Community Outreach on Inequalities in Physical Activity: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 12 January 2018, jech-2017-209882. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2017-209882.

Higgerson J, Halliday E, Ortiz-Nunez, A, Barr B. The Impact of Free Access to Swimming Pools on Children’s Participation in Swimming. A Comparative Regression Discontinuity Study. Journal of Public Health, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdy079.

Mason KE, Alexiou A, Bennett DL, Summerbell C, Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D. Impact of cuts to local government spending on Sure Start children’s centres on childhood obesity in England: a longitudinal ecological study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2021;75:860-866. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-216064.

Alexiou A, Mason K, Fahy K, Taylor-Robinson D and Barr B. Assessing the impact of funding cuts to local housing services on drug and alcohol related mortality: A longitudinal analysis using area-level data in England. International Journal of Housing Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.2002660.

Barr B. et al. The impact of contrasting investment strategies at the local level. Available at: https://sphr.nihr.ac.uk/research/places-communities/quantifying-and-evaluating-the-impact-of-contrasting-investment-strategies-at-the-local-level-wsa-wp2/ (unpublished analysis).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research School of Public Health Research (NIHR SPHR) and the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Northwest Coast (NWC ARC). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care or Public Health England.